maca, marina and martín’s mum, su: accounts from the world’s longest lockdown

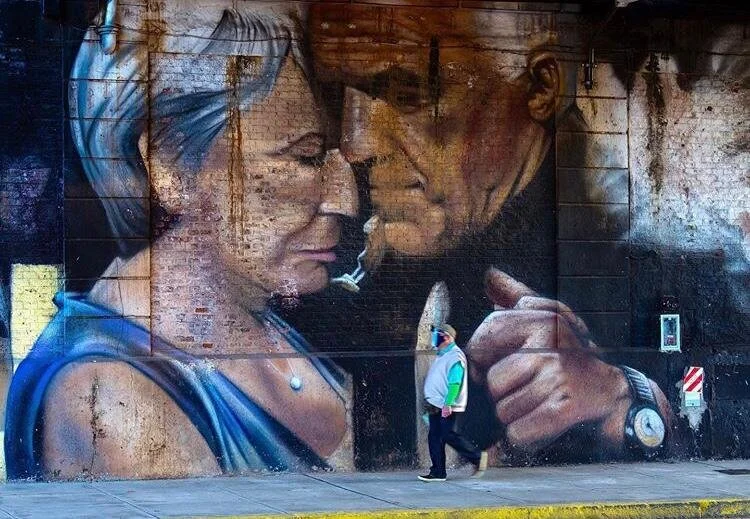

Photograph by Rodrigo Vergara.

In the first few weeks of my year abroad, my flatmates and I hopped on the 38 bus after work to go to see the final of the world tango championship. Partners sensually flung each other around to the rhythm of 4/4, eyes fervently locked in their close embrace and every pair a little more sensual than the last. After, the audience flooded out onto sunlit streets for an ice-cold pint and a chance to debate who they thought to be the best.

A year on, and the competition is still taking place, albeit a little differently to the last. Argentina’s tango talent is quite literally taking it to the streets as contenders film their entries in outdoor spaces – on cobbled corners, empty parks and high-rising rooftops. Tango is mostly improvised, after all; it is, arguably, improvisation which keeps the Argentine spirit alive. But given the South American country had one of the earliest and longest lockdowns in the world (210 days), Argentina’s dealing with Covid was far from an easy ride.

Sat at my desk in Edinburgh, watching leaves fall off the trees at an alarming rate and considering what an impending second lockdown might bring(or more appropriately, take away), I began thinking about Argentina’s incredibly long encounter with coronavirus, having spent half my quarantine stint in its capital. When talk of a national lockdown began, my Argentine friends and colleagues immediately told me to leave. Those old enough to remember the economic crisis in 2001, referred to today as the Great Depression, warned the same could happen again - maybe even worse. Having only really got back on its feet in the last few years, a wave of fear rippled across the Buenos Aires barrios on March 19th as the president announced the obligatory lockdown.

Maria Kopp is the founder of the NGO ‘Vientos Limpios’ which offer a wide range of support to those in need in her neighbourhood Villa 21-24, one of the poorest parts of the city. They provide daily snacks, healthcare, school support, and weekly cooking workshops, which I was lucky enough to be a part of during my work with a partnering NGO, Delicias de Alicia.

She tells me the first worry to cross her mind when lockdown was announced was her neighbourhood’s ability to cope throughout the lockdown on such low incomes. A bag of flour would be one price one week, and another the next. Inflation meant that the ability to predict or prepare for the future was incredibly difficult, even for the middle class. For those below the poverty line, who Maria dedicates her time working with, it was impossible.

Maca, the most amazing pal I met while we were both volunteering for the environmental NGO Eco House, shared similar concerns via our long-distance friendship’s saving grace – WhatsApp voice notes. “I worried about living in a country that was already in crisis, and now it has to deal with a pandemic too. What really worries me is what will happen later, with it being even more difficult to find work, more poverty and an even stronger social and political tension.” I think almost every 21-year-old worries about ticking all the boxes for their future at this age, yet Argentina’s crippled economy means disastrous hopes for Generation Z, and even the boxes to be ticked seem non-existent.

The lockdown was announced on March 19th, almost a week before it began in the UK. A city known for its noise was now silent; the only commotion being the occasional interaction between a taxi driver taking someone to the airport and a delivery man going the wrong way down the one-way street. Soon even this mid-afternoon entertainment would end, as the government announced the banning of domestic flights leaving and entering Argentina until September. Taxi-permission slips were no longer needed, and I was positively stuck in the city for the foreseeable future.

Lockdown afforded a lot of thinking time, which I talked about with Maca, Maria and my friend Martín’s mum, Susi, all of whom grew up and live permanently in Argentina. Su is from Quilmes, an area known for its famous beer but also for its poverty. Sheis the archetypal Argentine woman. Her first worry, she tells me, was how little anyone knew about the virus itself. The government’s message was simple but incredibly vague – ‘first we deal with the pandemic, then we will carry on with the rest.’ This ambiguity could perhaps be the reason it went on for so long despite the lockdown having begun so early on. The Argentines I knew did not care so much about catching the virus as much they did about losing their life’s work and savings due to the uncertainty it brought with it. In hindsight, experts have put the five consecutive lockdowns as a result of a failure to test sufficiently or use contact tracing, which meant that a later outbreak ensued. Such an outcome could not have been more damaging to the economy or the people. But, according to Susi, what was important to her still remained. ‘It taught me how family is everything’, she tells me, as she waits for the Uruguay’s to open so she can visit her 90-year-old mum.

My experience of lockdown in Buenos Aires was incredibly privileged compared to many.

One Sunday, as I was walking down the steps from the rooftop, I got a call from the British Embassy. We had just finished our weekly asado – an Argentine spin on the American BBQ, and probably one of my favourite things about the country’s heavily gastronomical culture.

After Juliet and I had done all the chopping, our Argentine flatmate, Sebás, would skilfully melt blue cheese into portobello mushrooms on the outdoor grill while we sipped Quilmes beers under the sun; a bit of a dream. It was an unconventional lockdown set up, with me, Juliet, Sebás and his cat Sultán --but I’ll cherish it forever. The chance to go back to England on a repatriation flight, which took months to organise by the government, was not that appealing to me. Buenos Aires, even in lockdown, had become home; I was not ready to say goodbye. But, with a lot of teary phone calls and countless pros and cons lists, I called the embassy once again (after having already rejected my first chance to leave) to say I would take it. ‘I’ll be back for another tango final’, I thought.

The ability to leave was something some of my Argentine friends really envied. They dreamed of moving to Europe and often questioned why we, English exchanges, loved their home so much. I could see a future here, but they couldn’t. This always seemed strange at first, but I knew it was deeper than the cheap pints and quality market stalls on a Sunday morning. The weakness of the Argentine peso and the ingrained instability of Argentina’s politics and economy took away the novelties we could not get enough of as exchange students. And Europe, for all its faults, undeniably offered far more opportunity.

As Buenos Aires starts return to a new form of normality, Maria is now able to work again with the people of her barrio, providing invaluable support at a distance. Maca tells me how she’s focusing on how she, as a young middle-class citizen, can make the situation a little better, reminiscing the Eco House slogan of ‘small actions x many people = important change’ that brought us together pre-pandemic. Susi looks forward to soon being back together with her ‘flia’, an Argentine word for her family of six.